Does the company have to build cars?

With the mature development of the industrial chain, autonomous driving companies can generally come up with autonomous driving sensor kits specially designed for Robotaxi scenes and in line with in-vehicle applications and standards.

In their view, building a car in the next stage is not only time-consuming and costly, but also has many technical barriers. It also needs to build its own factory and build an upstream and downstream industrial chain.

At the same time, there is another voice in the industry that adding sensor kits, technical units and software to the original vehicles is no longer in line with the next development goal of autonomous driving.

In other words, building a car will become the most critical step in promoting the commercialization of autonomous driving.

In July 2022, Baidu Apollo released the first unmanned vehicle RT6, which broke the dilemma that Robotaxi was mostly a modified car, and the cost of RT 6 was reduced to250 thousandYuan.

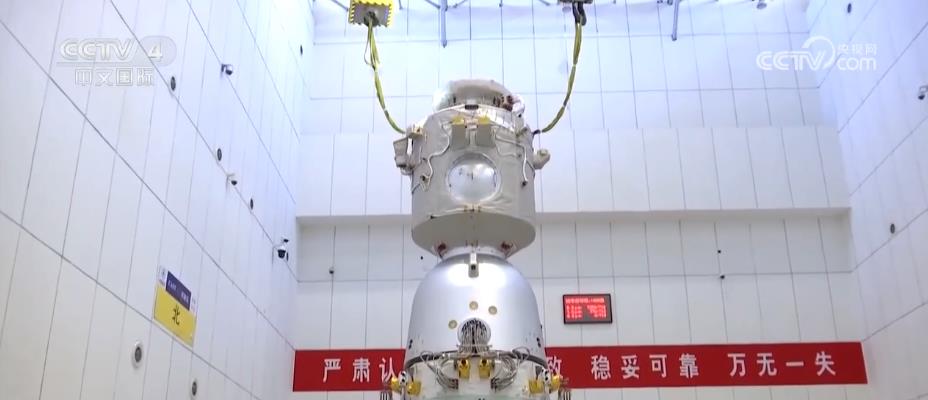

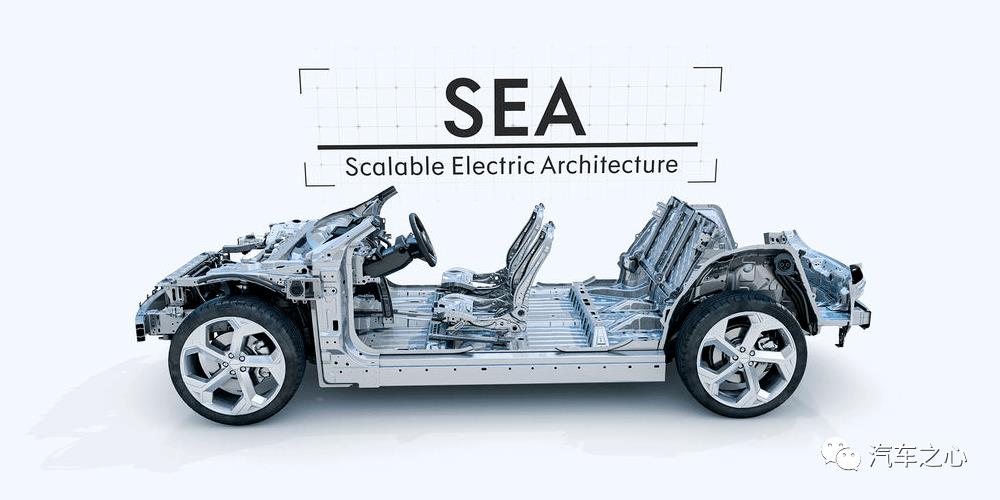

On November 17th, 2022, the M-Vision concept car jointly developed by Waymo and Krypton made its debut in Los Angeles. The new car was based on Krypton Vast-M.(SEA-M)The architecture will be mass-produced in 2024 and put into commercial operation in the United States.

In their view, autonomous driving wants to achieve large-scale mass production of technology, vehicle platforms need to be innovated, and software and hardware systems need to be more deeply integrated.

This means that the carrier of autonomous driving needs to draw a blueprint from a blank sheet of paper.

"It is an inevitable trend for unmanned vehicles to develop from refitting and installing finished vehicles to customizing and developing based on vehicle platforms. An industry person said.

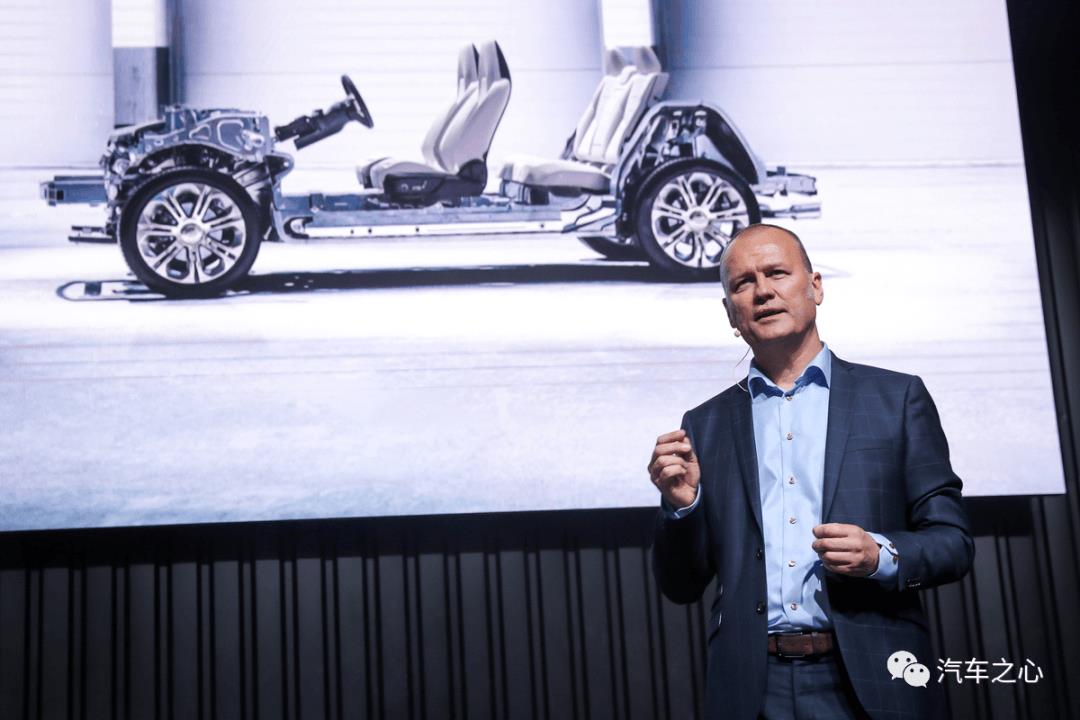

01、I started a sideline and built a car for Waymo.

In December 2021, Waymo officially announced a cooperation with Krypton. The latter will provide exclusive vehicles for Waymo’s self-driving fleet and put it into commercial operation in the United States.

A year later, the M-Vision concept car, the result of cooperation between the two parties, made its debut in Los Angeles.

According to the heart of the car, Waymo is responsible for the automatic driving system and cockpit entertainment system, while the European Innovation Center is responsible for providing the core components of Robotaxi.Vast -M architecture.

In fact, Krypton was able to cooperate with Waymo without two acquisitions.

In July 2021, it was extremely embarrassing.1,057.8 millionkoruna(about 799 million yuan) Acquired CEVT in Gothenburg, Sweden(China-Europe Technology Research and Development Center)100% equityLater, it was renamed the European Innovation Center.

After the acquisition, CEVT can provide shared architecture, chassis, powertrain, transmission system, car body and vehicle design technology for future strategic products and R&D platforms.

CEVT is a gathering place of technical souls.

Since its completion and operation in 2013, CEVT has been Geely.1.3 millionThe production and sales of this car provide a complete and systematic technical system, and have trained thousands of global technical talents. The well-known CMA architecture and so on are all from this R&D center.

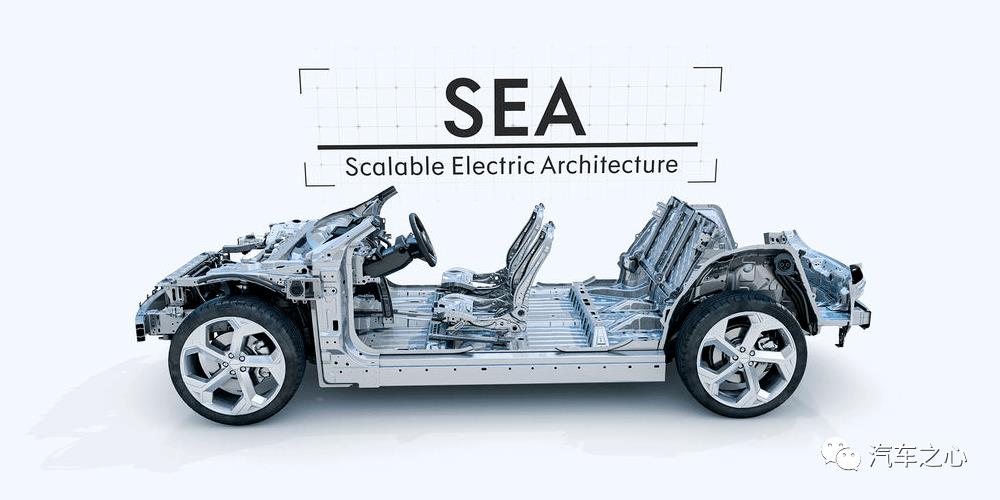

The second acquisition comes from the 30% equity acquisition of vast energy. This acquisition enables Krypton to redevelop the vast architecture of SEA.

In short, combined with the technical advantages of Krypton European Innovation Center, Krypton can develop the vast architecture again-this is also the origin of the vast -M architecture.

Vast -M is developed based on the vast architecture of Geely SEA, which took Geely five years to invest.20 billionThe pure electric architecture developed is also the killer of Geely in the field of new energy.

The characteristics of Geely’s vast architecture can be simply summarized into three key words:

According to Krypton, Haohan -M is the world’s first intelligent mobile travel platform specially developed for autonomous driving scenes, and it is the latest type of vast architecture facing the era of autonomous driving.

Among them, the m of vastness -M stands for Modular Mobility Architecture(Modular Travel Architecture).

On the basis of prototype architecture, Vast -M passedhardware layer+System layer+Ecological layerTo create a sustainable and extended self-driving vehicle.

To achieve this, we not only rely on the vast prototype architecture to cover the high application range of 1800-3300mm wheelbase of A-E class cars, but also need a native electric platform and flexible expansion ability to support L4 class automatic driving.

In this regard, it is almost impossible to achieve the traditional fuel vehicle platform, and related problems have been exposed in oil-to-electric vehicles before.

Constrained by a large number of complicated mechanical transmission structures, the expansion and layout adjustment capabilities of the traditional fuel vehicle platform are very limited, and the motors can only be installed in the space left after the fuel tanks are cancelled, so it is difficult to adjust the vehicle structure.

It can be said that holding the advanced vast -M architecture, he started a sideline business-helping autonomous driving companies build cars, which directly contributed to Waymo’s choice of cooperation.

Vast -M architecture, fully embedded with automatic driving interface, can be connected to the automatic driving system of L4 level and above, and can be compatible with different automatic driving schemes, from local control to full control of vehicles.

In addition, the vast -M architecture meets all technical requirements of autonomous vehicles and is compatible with all autonomous driving schemes.

"From Waymo’s point of view, it is extremely difficult for Krypton or Geely Group to find a second partner because of its ability to control costs under the same quality and its European R&D and innovation capabilities. 」

When talking about why Waymo chose to cooperate with Extreme Krypton to develop customized cars, Yang Dacheng, vice president of Extreme Krypton, said.

"The vast -M architecture is open to ecological partners around the world, not just Waymo, but also other global autonomous driving companies."

Through the cooperation case with Waymo, Yang Dacheng also threw an olive branch of "OEM" to other autonomous driving companies.

In the past, the threshold of "OEM" was not high, just providing enough assembly experience to achieve the production target.

Nowadays, due to the special products such as self-driving cars, the traditional cooperation mode is directly broken, and at the same time, the "OEM" needs to export certain research and development capabilities.

02、What’s different about Robotaxi, which Waymo cooperates with Krypton?

As a leader in the field of autonomous driving, Waymo has also tried to build his own car.

In May 2014, the autonomous driving team released a code-named ""fireflyThe unmanned car is planned to invest 100 vehicles in a small-scale trial operation in California in the early stage.

Due to the imperfection of the supply chain, the cost of Firefly is high, and the original 100 cars were finally cut down.50 vehiclesCar, coupled with the slow progress of the project, Google finally gave up its own car-making route.

In 2017, Google announced the retirement of Firefly.

In 2018, Waymo made an ambitious announcement to purchase from Land Rover and Fiat respectively. 20,000 vehiclesI-PACE and62,000 vehiclesDajielong is used to build a self-driving fleet.

In order to expand the operation scale of the fleet, in 2019, Waymo announced the establishment of the world’s first factory to produce L4 self-driving cars in Michigan, USA, which is mainly responsible for modifying the purchased existing production cars.

Up to now, there is no sign that Waymo has achieved his goal.

According to public data, Waymo’s current fleet size is only over 1,000 vehicles, and the current practice is still to install automatic driving kits on production vehicles.

This seems to be efficient, but it will bring many problems.

The first is the vehicle.Basic quality. The existing control system of mass production vehicles is built on the basis of human drivers, and the basic functions, including throttle, braking and steering, are all completed by traditional mechanical transmission, but this is completely different operation logic for the automatic driving system that relies on electronic signals to control vehicles.

Followed by the vehicle.Functional scene. Self-driving cars are essentially liberating drivers. Starting from the needs of passengers, we define what kind of functional scenes a self-driving car should achieve. However, most existing production cars are just a family car with comprehensive functions, and the layout of the cockpit cannot be changed, which cannot further expand the practicability of the vehicle.

Finally, the vehicle’scost. The needs of C-end users and B-end users are different. To build a self-driving car and a family car, the investment of BOM cost is completely different.

When refitting on the existing vehicle platform, it is necessary to bear all the BOM costs of the original private car, and it is also necessary to superimpose the cost of the autopilot kit, which is a great challenge to reduce the cost, which also leads to the large-scale investment of the refitted car and the cost of bicycles.

From the perspective of scale, Waymo urgently needs a mass-produced Robotaxi model.

In the negotiation with Krypton, Waymo once put forward requirements for vehicles-comfort comparable to S-class, chassis control comparable to e-tron, vehicle energy consumption comparable, and required the service life of operating trucks.

On the one hand, due to Waymo’s strong dominance, car companies can only play the role of engineering development and vehicle manufacturing.

On the other hand, based on Waymo’s personalized requirements for vehicles, car companies are reluctant to develop an exclusive self-driving car platform from scratch. After all, the current commercial feasibility is far lower than the research and development cost.

This is why Waymo’s previous cooperation model with car companies is relatively simple.

Waymo only purchases complete vehicles from Fiat Chrysler, Jaguar Land Rover and-,and deploys the sensor kits needed for autonomous driving on these vehicles through modification, and then carries out the real road test of autonomous driving or the self-driving taxi test.

Looking at the world, there are very few companies that can enable autonomous driving companies like Waymo to achieve mass production based on the vast -M architecture.

To put it another way, whether an autonomous driving company wants to build a car depends largely on whether it can find a useful carrier.

Based on this kind of thinking, a route that can not only be developed from zero to positive, but also hand over the burden of building cars to partners has become a new choice for autonomous driving companies such as Waymo.

The first is inProduct experienceOn the level, different from the traditional car model focusing on the driver’s thinking, the mobile travel vehicle built by the vast -M architecture is oriented to the automatic driving application scene, and the biggest highlight is reflected in the "user" experience:

The wheelbase of the vast -M architecture itself covers 2700mm-3300mm, and such a wide range of wheelbase makes the model extremely scalable-the front and rear suspension of the vehicle can be adjusted, and the distance between the seat and the rear axle can be stretched, finally providing a flexible layout of the cockpit space.

The second iscost. For self-driving cars, cost has always been the most sensitive issue.

A modified model with an automatic driving system, the price is500-1 millionRenminbi. In this cooperation with Krypton, Waymo’s demand is "to get the best things with the least money".

Yang Dacheng said, "Based on the efficient universality and scale of the vast architecture itself, the vast -M architecture can meet the needs of users with different budgets. 」

The third isquality. M-Vision meets the global five-star safety standards and conforms to the American Highway Safety Insurance Association.(IIHS)Maximum safety requirements. M-Vision can guarantee 500,000 kilometers in five years and meet the requirement of 16 hours of uninterrupted operation every day.

As early as the launch of the vast architecture, Geely said that the vast architecture will launch products with full open road autopilot function in 2025.

The debut of M-Vision also marks the further verification of the intelligent planning of the vast architecture.

03、Extreme krypton press the "fast forward key"

Waymo provides autonomous driving technology, and Krypton provides highly customized exclusive vehicles-this cooperation mode provides a new problem-solving idea for the landing of autonomous driving.

In addition to Waymo, other autonomous driving companies can also realize the landing of autonomous driving products based on the vast -M architecture.

As the most important smart electric vehicle brand under Geely Holding, through the commercial cooperation with Waymo, the vast -M architecture can also be fed back to the passenger car market in the future, thus enhancing the competitiveness of the brand.

Not long ago, Yang Xueliang, vice president of Geely, revealed on the social platform:

"M-Vision is a customized Robotaxi for Waymo in the United States, and M-Vision also has plans to promote To C products. 」

It is understood that the vast -M architecture will retain two versions of steering wheel, pedal/steering wheel and pedal at the same time.

According to informed sources, there are currently two products under development in the vast -M architecture:

With the continuous growth of the launch and delivery of the second new car 009, the product matrix of Krypton is accelerating.

According to the previous plan, Krypton will cover cars, SUVs and sub-categories around three product lines: Z, C and M in the next two years:

At the same time, Krypton will enter the global market, and Krypton 001 will enter the European market in 2023.

At the beginning of its development, Krypton fully considered the European standard and American standard, and certainly did not rule out a larger scale in the future. Extreme CEO An Conghui said.

Behind the market opportunity game, production capacity is the key to break through.

"Krypton currently has a production capacity of 300,000 vehicles, so it is no problem to ensure production and delivery, because we have other factories. In recent years, the new factories have also comprehensively considered the production needs of electric vehicles, and can realize the manufacturing of vast architecture products in the fastest time. At the press conference of Krypton 009 in November this year, An Conghui said.

Up to now, Extreme Krypton 001 has become the sales champion of China brand 300,000 luxury pure electric vehicles for three consecutive months-a total of 60,000 vehicles have been delivered, and the average order amount has exceeded.336 thousand.

Through the performance of krypton sales, An Conghui’s "internal letter" to internal employees shows that:

"The success of a single product cannot bring about the sustainable development of a brand. The diverse needs of users require us to complete the product layout from single product explosion to multi-product development as soon as possible. 」

Different from the cooperation mode of the new forces in the head and the internal incubation mode of traditional car companies, it relies on Geely+Volvo’s car-making experience and technical resources, but from decision-making to the accumulation of marketing experience, it has gone through a complete process from 0 to 1.

In other words, Krypton is exploring a route that combines the technical background of traditional car companies with the flexibility and efficiency of new cars.

As you can see, based on "Geely+Volvo technical resources are the underlying logic.",as well as the self-evolution of users’ travel needs, it is accelerating to prove the feasibility of building a third track.